Here’s my happy story for when this happens:

When working on an assignment for two merged government agencies, my team and I lucked onto a research specialist who had started her career as a records manager in one of the two agencies. She later become head of that agency’s records unit, and while in that job, she acquired a master’s degree in research organization and management. Then she moved into a job in the research unit of the other agency, about two years before the agencies merged.

Our team’s assignment — as external consultants — was to work with management and staff to develop a knowledge strategy for the “new” agency. We liked the idea of the assignment (or we wouldn’t have accepted it) and we looked forward to conducting the knowledge audit, putting together our findings and using those findings to frame our recommendations, developing a knowledge strategy, and designing the implementation plan for knowledge services for the “new” client organization. Our only concern had to do with how we would convince all agency stakeholders — from two former agencies remember — that with major change on the horizon the success of the merger would require a critical collaboration effort. How would we get everyone on board?

We needed an ambassador, an advocate. And there she was, right on the premises. As we spoke with her about our recommendations for moving forward, she knew all the language at play in the former agencies (now just the one). She also knew — for which we were grateful — where the barriers were (where “all the bodies are buried,” as she cleverly put it). As we talked, with her at the head of the working group in charge of the transition to the new knowledge-sharing structure, she reminded everyone that the effort would only work if we could confirm the value of the agency’s built-in, internal knowledge content. As important as anything else, she stressed, we had to establish that that knowledge value would determined by the expertise of all knowledge workers in the agency. And how well they demonstrated that expertise.

We needed an ambassador, an advocate. And there she was, right on the premises. As we spoke with her about our recommendations for moving forward, she knew all the language at play in the former agencies (now just the one). She also knew — for which we were grateful — where the barriers were (where “all the bodies are buried,” as she cleverly put it). As we talked, with her at the head of the working group in charge of the transition to the new knowledge-sharing structure, she reminded everyone that the effort would only work if we could confirm the value of the agency’s built-in, internal knowledge content. As important as anything else, she stressed, we had to establish that that knowledge value would determined by the expertise of all knowledge workers in the agency. And how well they demonstrated that expertise.

So without knowing it, she was already the knowledge thought leader with respect to research management for the merged agencies, and now she could combine those two lines of work into a single function. So of course — with management’s permission — we brought her in as adviser to our consultancy team, as an in-house consultant and resource person. Needless to say, she knew everybody we needed to know, and she — of all people — knew who the influential management leaders were (she had long ago identified them). Working with our consultancy team, this records manager cum research specialist not only provided enormous value to our project, but the new agency’s leaders trotted her out to speak to other agencies about what we had done, about lessons learned, and to advise about how to ensure that research management was recognized as the critical operational function it is. She led the recognition effort, developing and implementing a structured awareness-raising strategy, and she’s never been thought of as anything but the agency’s knowledge thought leader since.

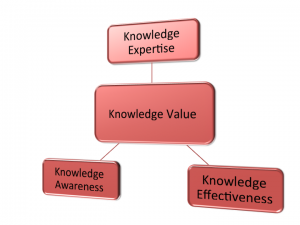

So what was the shape of her success? If I may be excused for being a little self-serving, it’s a notion I put forward in a book that’s now almost 20 years old: It was called Entrepreneurial Librarianship: The Key to Effective Information Services Management (if I were writing this book today I would call it Entrepreneurial Knowledge Services). What I proposed — and what this new agency’s knowledge strategist put forward — was a two-part framework for strengthening knowledge value within the organization, basing knowledge value on knowledge expertise. Part One — I recommended — was to ensure that everyone in or affiliated with the organization was aware of the role of knowledge value. Part Two — following on naturally — was to expand the link to establish that together knowledge awareness and knowledge value lead to organizational effectiveness.

How did she do it, this leader in research management in the now-merged government agencies? How did she establish information value? Knowledge value? The value of strategic learning? Or, in our terms, knowledge services value? What was her approach?

Simple. She asked five questions about the management of information, knowledge, and strategic learning, and she combined them all into one subject, all under the general rubric of knowledge services:

- Who needs it?

- What do they need?

- How do they get it?

- Is it satisfactory to them?

- Do they know how it gets to them?

With those five questions answered, her agency’s route to knowledge effectiveness was assured.

Leave a Reply